Eszter Steierhoffer

Interview with Madelon Vriesendorp

2023

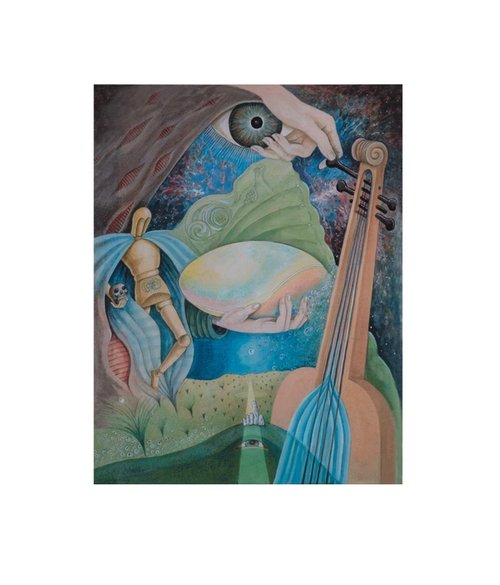

Madelon Vriesendorp is a Dutch artist, sculptor and collector. A founding member of the Office for Metropolitan Architecture (OMA), her graphics and anthropomorphic architectural paintings provided important visual context to OMA in its early years, and her drawings and illustrations have been significantly influential for generations of architects ever since. Mainly based in London since 1976, Madelon has been working across a wide range of media on the expanded field of architecture, including costumes, built objects, paintings, murals, exhibition design, illustration, and short stories. Cosmic Housework, Madelon’s site-specific exhibition at The Cosmic House brings together her already existing pieces with new works. The exhibition offers a playful (re)interpretation and humorous subversion of the symbolism imbued in the architecture of The Cosmic House, densely packed with ideas and motifs embracing an entire cosmos of architectural allusion, history, metaphor and reference. In this interview, Jencks Foundation Director Eszter Steierhoffer discusses her new work and exhibition on view from 12 September 2023 to 31 May 2024.

Eszter Steierhoffer (ES): Your exhibition ‘Cosmic Housework’ unfolds as a dialogue between two minds – friends and collaborators – and reveals a shared sensibility that can be traced through your collaborations, such as the iconic drawings for the cover of Charles’ Story of Post-Modernism or the illustrations of the ‘enigmatic signifiers’. The show also includes some of your most recent body of work, ‘Plastic Surgery’ (2016 – present) which lends new meaning to domestic materials otherwise seen as useless or unprecious, and which continues in the tradition of your previous work challenging established norms and the canon. The Cosmic House itself subverts the domestic and the banal through its use of irony and double coding, and you have been a frequent visitor to the house since the early 1980s as your friendship with Charles spanned more than five decades. Today the house is a museum, and you have been invited to inhabit its public spaces with your work. Could you talk about entering into this posthumous conversation with the world of Charles that The Cosmic House represents?

Madelon Vriesendorp (MV): In my work with Charles, we were always focused on making visualisations of his theories and ideas. This exhibition is the first time I see my own work and his together, and see the ways in which we are connected. We are both interested in symbols and their power. We both collected objects and surrounded ourselves with them to create imagined lives with all available materials. We had a mutual love of both high- and low culture. and their combination.

In a way, we were each other’s opposite. I was a European fascinated with Americana and kitsch. He was an American fascinated with European culture and the classics. He liked things to look luxurious, I like things that are cheap. But our tastes met in the middle; we both had a love of ersatz. We liked things that were trying hard to be other things. I loved including marbling in my paintings, as did he throughout his entire house. The objects that I make now are attempts to elevate discarded and disused things, such as toilet- or kitchen rolls and milk cartons, and to turn them into beautiful or interesting objects. It’s almost like giving them a drag makeover. Charles likewise wanted to elevate everything to a mythical or cosmic level. His living room became a portal to the universe. He once sent me a cartoon of a man with a knife in his back in the doctor’s surgery. Facing him across the table, the doctor says, ‘Good news. The test results show it’s a metaphor’.

I think Charles would love this exhibition, because he courted opposition and challenge.

ES: Do you remember when you first met Charles?

MV: I met Charles because he was my husband Rem’s teacher at the Architectural Association. He discovered Rem as a funny thinker and they became friends because they were both outsiders and nonconformists. Charles loved provocation and controversy. He would invite Rem to dinner so that he could argue with other architects, and I would just come along. I got along really well with both Maggie and Charles. Maggie liked my work; she bought one of my etchings and we became friends. Eventually we went on family holidays together. Maggie would buy us aeroplane tickets to visit them in the south of France, because she knew that we had no money. She was incredibly generous and caring.

ES: Why and when did you start working with Charles?

MV: It started when Rem and I were at dinner with him sometime in the 1990s and he was working on a park in Milan in which he designed a curved lake. I looked at the plasticine model of it and I said, ‘No, this curve is wrong, it should be like this.’ I grabbed the model and adapted it, and then Charles said, ‘OK, can you come tomorrow?’ And from then I started to work with him making models, and his cartoons to illustrate his book on Post-Modern architecture. He would explain his theories and ideas, and I would draw while he was talking. He realised that I could translate his ideas and metaphors into images. We laughed so much about what we came up with. We were connected by our sense of humour. He was the architect and intellectual and I was the artist, we complemented each other and laughed about the other’s and our own madness.

ES: In an earlier interview about Charles you said there is no invention without humour.

MV: There's something about humour and invention. Often funny people can see the connection between the real and the imagined. That is what invention is – it is sort of seeing what the possibilities are between ideas or objects.

ES: The two type of projects you collaborated on are cosmic garden designs (several of them) and the book The Story of Post-Modernism (2011). You made a painting for the cover, and cartoon-like ‘enigmatic signifiers’ to illustrate Charles’ term for iconic buildings and their potential to pertain to multiple symbols and a plurality of meanings. But your drawings are more than illustrations: they reveal a dialogue between the two of you, and your shared sensibility around humour, irony and language. They are also heavily reliant on a graphic language and tradition that you established through your earlier artworks and graphics.

MV: I had already worked in different disciplines – illustrations, book covers, etchings, painting architectural drawings – and understood the mind of architects and writers. Charles was very much into literal explanations of things. So I just played with that and put everything on paper in a literal way. But they were very much his ideas – I just made fun of them. I made other drawings that he didn't use; just jokes between the two of us, and we laughed together a lot. We were both fascinated by symbols and psychoanalysis and surrealism. We were also both interested in the way that different cultures have different sets of symbols, and how if we made combinations of symbolic systems, just because they would subvert symbolism and language.

ES: Can we say that in some ways you were translating Charles?

MV: Maybe I tried to turn his ideas into visual language, so I wanted to be true to his ideas. And yet he liked that I would tell him when I thought something was bad or ugly. He was great at taking criticism and laughing at himself, and also telling stories about how he had been insulted by people and just laughed. And he often invited people who didn't agree with him at all. He loved that controversy; he was extremely excited about all the interactions and different opinions of people, and about what happened when they clashed.

ES: You both had immense respect for each other's work, and you shared a lot, not only a sense of humor, but also a deep curiosity and drive to learning from elsewhere, from the banal, and being able to notice what others overlooked. What do you think you might have brought to Charles’ world?

MV: I was not like all the serious men around him. As a woman, he could be playful and unserious with me. I think that Charles and I both questioned why some things are valued more than others. We brought together high- and low culture, and loved to witness the clash between things that are considered important and things that are considered irrevelant. You could call this the banal, possibly artists always seek to reinvent the banal. We loved it when things failed, when objects that hoped to be grand actually looked ineffective. And we loved tackiness, even though he appreciated grandeur much more than I did.

ES: And what did you learn from Charles?

MV: He was always telling me about the cosmos and psychology, and he taught me so much. He gathered information, but he never told me anything twice. He had an unbelievable amount of amazing stories and facts, and every time there was a new discovery he read about in magazines. He cut out from every magazine on his many trips. And that's why he has books full of articles. He was like the Internet before there was an Internet. He was sort of like the little boy in class who always puts his hand up. I really miss the way in which I could ask him about anything and he would explain it clearly. That’s the sign of genius: to be able to explain complicated things in simple words. Few people can do that.

Charles was one of the greatest supporters and believer in my work and he taught me to value it. For many years after I left OMA I stopped painting, and he was the person who really tried to get me painting again. He not only liked my work, but he really valued my opinion and my input into his own work. He would always credit me, sometimes too much; at some events he even made me stand next to him. He was an extrovert, but that never made him compromise his generosity. He truly believed in the value of collaboration, and that’s sometimes underestimated today.

ES: Cosmic Housework is a playful dialogue with The Cosmic House, and it centres around some of your collaborations with Charles. It also features elements from your most recent series, titled ‘Plastic Surgery’, which I believe is exhibited publicly for the first time here. Could you speak more about when and why you started to develop this new body of work?

MV: A mother is relegated to the house. An artist sees the potential in everything around them. That’s why they collect images and materials, because they believe any object, every material, has the potential to become something else. For example, I love that you can put Tipp-Ex at the ends of grape stems to make them look like trees. When I had children, my house became filled with toys. Before OMA, I had already worked on illustrations, paintings and collages for architectural concepts. So when I became a mother, my work changed as my focus changed. I put the two sensibilities together. I started making architectural models – which eventually became entire cities that covered the surfaces of my house – out of the objects and the toys in my home. I merged my domestic setting with my drive to make things. Female art forms have often been labelled craft for this reason, because they inhabit the domestic sphere. I am interested in craft and therefore I have often collected street craft from around the world. In poor countries, children make their own toys from whatever they find, and poor artists make beautiful objects out of mundane and inexpensive materials. Their crafts often express their culture better than the more valued ‘high’ art. I consider my work with cardboard and plastic as a type of craft.

ES: ‘Plastic Surgery’ is a new chapter, but also an obvious continuation of your earlier work and interest in found objects. Its elements are humorous and also quite subversive, in that you are reusing domestic waste and turning it into beautiful intricate objects.

MV: ‘Plastic Surgery’ is a series of sculptures that I made out of plastic milk bottles. I love the material – milky plastic. My friends are always bringing bags full of their empty bottles for me to turn into sculptures. Among my friends, they have become a valuable commodity. We are living in the plastic age. We are ingesting plastics, we are filling our bodies and our food with it and we are creating entire Islands out of our plastic waste. And yet I want to show how every bit of plastic packaging can potentially become something wonderful. It can take on a life of its own. I think this rethinks our relationship to plastic: to respect it rather than consume it. I'm sharing my attempts at, not so much recycling as, reinvigorating these momentarily useful but generally catastrophic objects.

Maybe this sense of valuing the worthless stems from the fact that I was born at the end of the Second World War. In Holland there was nothing left. My father had crafted wooden tires for bicycles all through the war, as there was no rubber. For this reason I might have a reluctance to throw things away, because there was such a shortage of everything. So as children, we were always making things out of cardboard or matches and whatever we could find. It was not such a strange thing for me to go on doing that. When I had children I made toys for them: furniture out of packing material. Every time we went to the toy shop and they wanted something, I would say, ‘We can make that’. And usually I could. I think I learned this practicality from the need of my childhood.

I love that I have power over discarded and forgotten things. I love the challenge of finding something to do with them. I look at a plastic bottle and think, ‘Who and what is hidden inside this form’, and then I try to bring that character out. I start by making faces – that instantly brings an object to life. Eventually I give them clothes and then homes. One time I made a swan out of a milk bottle, and I kept making more and more, and then the swan population grew and then they needed a pond, and when they started to fall out of the pond, I realised the madness of it. And that often happens to me, that my objects start to populate my house, and their numbers grow out of control.

ES: Cosmic Housework is an oxymoron, and a pun on Charles’ ‘double coding’ that mixes together high and low, the domestic with the cosmic. Where did this title come from and what does it mean to you?

MV: If you're a woman and a housewife – working in the house your whole life – you have done housework for decades. And yet this type of work is the least valued, even though it never ends. Because the domestic sphere has become demoted to an afterthought, a prison even. And yet I see inspiration in the domestic. The lifeblood of housework comes in disposable plastic bottles and jars, so all the things that I use are part of the remnants of housework. I clean all the bottles, and am forever peeling labels and keeping the packaging that we might usually recycle. They are essentially domestic objects that I have elevated to the status of art. Charles did the same with his house: he used the domestic space in which he lived to test his ideas. We turned our homes into new worlds – fantasy spaces – by using our collections of objects or by painting the materials in our homes and transforming them into something more luxurious.

For me, the difference between artwork and housework is the difference between individualism and collaboration, public versus private, the grand and the irrelevant, seriousness and humour. Charles and I always wanted to blur these distinctions, because one is always valued more than the other, but sometimes the lesser valued is of cosmic significance.1

A phrase that Ian Kirk coined so beautifully.